East or West?

Anna sits, as she does so often, watching her television. She sees the Sultan clad in his magnificent clothes dispensing judgement upon those being brought before him, and she holds her breath as she waits to hear the fate of the gorgeous doe-eyed beauty that prostrates herself in front of this potentate. Anna knows that this is pure escapism. It is a bid to remove herself from the harshness of her life in Pireaus. She is aware that it is but an attempt to distance herself from the cold and the starvation and the privations that the Crisis has brought upon her and her family.

It is getting dark and she gets up to light a candle. She smiles wanly at her involuntary movement towards the TV remote. There has been no electricity here this last three months. The Sultan and his retinue creep quietly back into the depths of her imagination.

Do not imagine that this situation is rare in the Greece of today. But what is perhaps interesting is that Anna’s imagination takes her to Turkish television and the programmes she used to watch when she had electricity. This is the case for the majority of Greek people. Their favourite ‘soaps’ are Turkish, with Greek subtitles. But why should this be?

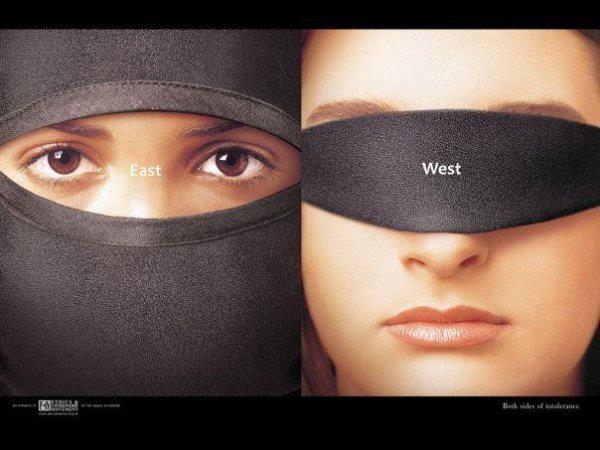

Well perhaps the strangest thing about that question is that we should have to ask it. For it is a Western European question, one that comes from our long-held expectations of Modern Greece – and how misguided we are in those expectations. There are two Western European views of Greece, firstly the ‘Classical’ one and secondly the ‘Sun/Sea/Sand/Sex’ one, and these two overlap slightly.

The Classical view is that which the educated classes of the Western world have propounded for the past three centuries or more. That there is a country called Greece which holds all the attributes of Ancient Greece – that wonderful culture that gave us our own civilization. The Golden Age that offered us the kernel of true democracy, architecture, philosophy, mathematics, and so much more. Generations of Westerners have been schooled in the Classics, and have learned to read Ancient Greek. They thus have philhellenism in their hearts.

This was no mere scholarly feeling, for such was the Western fixation on the idea of a revival of (Ancient) Greece that the Great Powers of the time – England, France and Russia took it upon themselves in the mid nineteenth century to help those that occupied much what is now southern Greece defeat the Ottoman Empire and form the Modern Greece of today.

But what was this Greece? Where did it come from? An Englishman’s grasp of history beyond the shores of our own islands is a woeful indictment of our educational system. There is perhaps a general awareness of the Roman Empire and a sort of vague recollection that is was ‘over-run by Barbarians’ in about 450AD. Whilst this is, to an extent, true it is only so of the western portion of the Roman Empire. That there was a division of the Roman Empire in 395 AD has escaped most of us, although it led to perhaps the most successful and influential Empire of all time and the one that kept the candle of civilized values burning for the thousand years that it took before Western Europe picked up that baton.

The Byzantine Empire was, initially at least, Roman, but its official language, and that of most of its vast population, was Greek. Not Ancient Greek, but something more akin to the Greek that is spoken today. The richness of its culture owes more to the influences of the East than those of the West for its capital Byzantium, later Constantinople, now Istanbul, stood at the crossroads of civilizations and its influence extended to all its peoples, including the area of land we now know as Greece.

The Ottoman Empire finally defeated Byzantium and took Constantinople in 1453 It was a regime inspired by and sustained by Islam. But it was not at all zealous in insisting that its population should subscribe to that religion. Its success was in no small part due to this tolerance and the autonomy it offered to individual states and peoples – provided they paid their taxes, thus they encouraged the immigration of Jews from Spain to Thessaloniki. But again the culture of this new regime was even more Eastern than Byzantium, indeed the newly emerging Western culture saw the Ottomans as their enemy.

So from 395 AD to 1830 the land that we now call Greece was influenced almost entirely by eastern culture. Furthermore the Great Schism of the Christian Church in 1054 formalised the position of Greek Orthodoxy as quite distinct from Roman Catholicism, thus confirming Greece’s separation from the West

The romantic notion of Ancient Greece as propounded by Lord Byron and his fellows led to a construct, a state founded upon an almost mythical idealism, as exemplified by the German promotion of Athens, then little more than a village, to be the capital of Modern Greece. The expansion of the country in 1912 to include what is now northern Greece added a population with an even more Eastwards orientation.

The ‘Sun/Sand/Sea/Sex’ view is simpler than the Classical one. This country of less than 12 million people is host to some 17 million tourists every year. For five decades or more western Europeans have flocked to the beaches, especially the island beaches, of Greece. They arrive by plane. It is no more than a three-hour journey, and they stay in resorts that ooze with western trappings. When these holidaymakers return with their suntans and tales of this gorgeous land they have not even scratched the surface of the culture. To them it is an adventure to a country where the road signs are written in a funny script. Apart from that it is as western as their own country, and most regard Greece as being much the same as Italy, but a ‘bit further along’. Such is the arrogance of the West that we do not listen, we do not see, and above all we do not understand that which we experience.

Both these views combine to provide the illusion that Greece is a Western European country. And the situation is reinforced because the ‘elite’ of Greece, those with money and/or political power are educated in the West. Most well-to-do Greeks have spent time in Western Europe or the States, either as students or working as professional or business practitioners. And they, most particularly the politicians, have propelled Greece unrelentingly Westwards. Venizelos did so in the early C20th, and Karamanlis followed his example in determining that Greece should join the European Union (then very much a Western club) which it did, as the community’s 10th Member in 1981. Membership of NATO (1952) and Greece’s inclusion in the Eurozone (2001) has placed the country firmly within the Western fold.

And yet Anna looks East for her entertainment, for such is her culture, a culture that has been ingrained into the population throughout the best part of two millennia. Just over a hundred years ago this city of Thessaloniki, from whence I am writing this, was Ottoman. Whilst the politicians of Greece and Western Europe are as one in seeing Greece as a Western country, her population hold within their hearts a more Eastern, or at least Balkan, culture. It is a largely unrecognised dichotomy.